David Marcum is known to fans of Sherlock Holmes, at least partly as the editor of the MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes series, which collect “authentic” Sherlock Holmes pastiches, published in handsome volumes, the profits (including the authors’ royalties) from which go to help Stepping Stones, the school currently occupying Undershaw, the house designed and built by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. He also writes Sherlock Holmes pastiches of his own, as well as those featuring Solar Pons.

But David has many other strings to his bow, and one of them is an interest in John Thorndyke. For those unacquainted with this “medical jurispractitioner”, a little later than Sherlock Holmes, Thorndyke, created by R. Austin Freeman, is a very scientific detective, with much more in common with modern forensic practice than Holmes. Starting life as a doctor, Thorndyke later proceeded to the bar (became a barrister), and brought a scientific rigour to the cases in which he appeared as an expert witness.

But David has many other strings to his bow, and one of them is an interest in John Thorndyke. For those unacquainted with this “medical jurispractitioner”, a little later than Sherlock Holmes, Thorndyke, created by R. Austin Freeman, is a very scientific detective, with much more in common with modern forensic practice than Holmes. Starting life as a doctor, Thorndyke later proceeded to the bar (became a barrister), and brought a scientific rigour to the cases in which he appeared as an expert witness.

David, with a background in investigation and forensics, has just completed editing a collection of the original Thorndyke tales, and I asked him a few questions about this project, and related issues:

If you were an official police detective working on a case, who would you sooner have working at your side, John Thorndyke or Sherlock Holmes?

The short answer is Dr. John Thorndyke, although it pains me to pick him over my hero, Sherlock Holmes. Having grown up around detectives and policemen (see below), I know that their disdainful attitude toward private detectives and amateurs that is portrayed in books and film is accurate. The police have a procedure that must be followed in order to document everything to make a court case that can’t be picked apart. The chain of evidence is sacred – or supposed to be that way. Also, there’s a feeling that if someone could really do the job, they’d be on the official force. Private detectives are usually a joke at best to the police in the real world.

The short answer is Dr. John Thorndyke, although it pains me to pick him over my hero, Sherlock Holmes. Having grown up around detectives and policemen (see below), I know that their disdainful attitude toward private detectives and amateurs that is portrayed in books and film is accurate. The police have a procedure that must be followed in order to document everything to make a court case that can’t be picked apart. The chain of evidence is sacred – or supposed to be that way. Also, there’s a feeling that if someone could really do the job, they’d be on the official force. Private detectives are usually a joke at best to the police in the real world.

We had a private detective in my home town, a one-armed man who had also previously been the leader of the local Ku Klux Klan group. His vehicle license plate said Im 007, and he had a house full of silly listening equipment and other tools of his trade. He would often butt in on cases to express ridiculous theories, but the newspapers would eat it up. Once, in my capacity as a federal investigator, I had to interview him. He insisted that we sit in his Im 007 car so that any listening device that I might be wearing (which I wasn’t) would be blocked. While we sat there, I began to be covered by tiny baby spiders that were crawling up out of the car seat. Without missing a beat of whatever nonsense that he was telling me, he began reaching over with his one arm and picking off the spiders and popping them, one by one, until we were done. That’s my real-life encounter with a private detective in action.

Part of what makes the Holmes stories so fun is that he sees what others don’t, and sometimes those others who aren’t seeing are the official force. When the first Holmes adventure was published in 1887, the idea of preserving a crime scene, or approaching a crime scientifically, simply wasn’t done. And yet, as time passed, the police adopted more modern methods, including some that were originally described in the Holmes narratives. By the later Holmes stories, the Yard was attempting to do things the right way, and Holmes had gone from being an outsider who was laughed at behind his back, despite his successful results, to someone that was admired. As Inspector Lestrade said at the end of “The Six Napoleons”:

“We’re not jealous of you at Scotland Yard. No, sir, we are very proud of you, and if you come down to-morrow there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand.”

By the time Dr. Thorndyke came along, the Yard was well along toward embracing scientific detection. In the first book in the series, The Red Thumb Mark (1907), Thorndyke and his friend Dr. Jervis visit the Yard’s fingerprint department. Nothing like a fingerprint department existed in Holmes’s day. Thorndyke is still something of an outsider, able to see and do things beyond what the Yard can accomplish, but he’s also a welcome co-investigator, instead of someone like Holmes in the early days, who lamented the stupidity of the police.

I remember discussing The Body Farm with you some time ago, and so I know that some members of your family have had some real-life forensic experience. Would you like to provide a little more detail about this? And how has this knowledge and experience influenced your attitudes to crime fiction written before the advent of modern forensic practice?

For someone who is interested in mystery stories, I grew up in a very interesting way. Or possibly the way that I grew up gave me an interest in mysteries. My dad was a Special Investigator for the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, covering a multi-county area, and assisting other local law-enforcement agencies when they needed help. He had been an MP in the Army during the Korean War, and then he became a Highway Patrolman before becoming a TBI Agent when I was just two or three years old, in the late 1960’s.

Because he covered a number or rural counties, his office was in our home. There he kept all of the equipment that he’d need, including his fingerprint kit, crime scene investigation tools, blank forms, and evidence collecting items – and also the files of all his cases, in two big filing cabinets. He would let me read those files, starting when I was around eight years old, pulling one after another out of the drawer, as long as I was careful with them. I was probably much too young to see that stuff, but I don’t regret it. (One of his most lauded cases was the murder of a rural country doctor by way of a sawed-off shotgun fired close-range at his head. The extremely graphic photos were all in the file, and when I read about the same type of murder in the Holmes adventure The Valley of Fear a year or so later, I knew exactly what it looked like.)

In addition to letting me read his casefiles, he would occasionally take me on investigations with him. He taught me how to obtain a subject’s fingerprints, and to lift them from an object. I saw him conduct interviews – and in hindsight I wonder how it was managed that I could sit in on them – and once he took me to a murder scene. While there, I found what I thought was a blood stain well away from the action and was sure that I’d discovered an alternate route as to how the body was removed. I went and pestered the “blood expert” to come look, and he informed me that instead of a blood stain, it was the droppings of a bird who had been eating berries. Thus ended my big Ellery Queen moment on one of the Inspector Queen’s cases.

For a while as a kid, I established my own detective agency in a big walk-in closet in our basement. Some neighbors actually “hired” us, and the little money that we earned was rolled back into the business in the form of office supplies. To help us, my dad gave me a bunch of his official forms – blank fingerprint cards, evidence collection stickers, and so on. He also regularly received FBI Wanted Posters in the mail, and he passed those on to me. I hung them in our office.

Later in his career, my dad became the first TBI polygraph (lie-detector) operator in the state. When he would give demonstrations to public groups, he would take me along as his guinea pig and hook me up as his subject to avoid the liability of asking strangers questions. When we would demonstrate at my school, I usually received very embarrassing questions yelled out from my peers about which girl that I had a crush. That wasn’t fun, and also it was usually very revealing to the girl.

My dad had several notable cases over his career, and one was written up in a “True Crime” type magazine, but one big career accomplishment was that he was the first to use Dr. William Bass, the world-famous forensic anthropologist, as a consultant related to dead bodies, back when Dr. Bass was simply a college professor. When he retired, my dad received a commendation from the state for his entire career, including having that idea to involve Dr. Bass in a case. This involvement led to more work of the same type with other agents, and eventually Dr. Bass became so intrigued that he created “The Body Farm”, a world-famous site where decomposition of human remains can be studied under all types of conditions. It’s located about fifteen miles from where I live.

My dad had several notable cases over his career, and one was written up in a “True Crime” type magazine, but one big career accomplishment was that he was the first to use Dr. William Bass, the world-famous forensic anthropologist, as a consultant related to dead bodies, back when Dr. Bass was simply a college professor. When he retired, my dad received a commendation from the state for his entire career, including having that idea to involve Dr. Bass in a case. This involvement led to more work of the same type with other agents, and eventually Dr. Bass became so intrigued that he created “The Body Farm”, a world-famous site where decomposition of human remains can be studied under all types of conditions. It’s located about fifteen miles from where I live.

I’m very glad for this experience growing up, and how some of it helped prepare me for my first career as a federal investigator with an obscure U.S. Agency, now long defunct. Personally, seeing all of these things in real life has really given me an added perspective when reading crime stories – whether it be the Great Detectives like Holmes, Nero Wolfe, et al, or other books that focus more on police procedures. I understand that, even as investigation becomes more and more about gathering evidence, there is still a human component that can’t be ignored.

Connected to the above, I was talking to a former police officer the other day who was bemoaning the fact that (in the UK at least), most crimes are solved and convictions obtained, not through detective work, but through DNA analysis or CCTV footage. In your opinion, could this be a factor for the enduring popularity of the more “human” detective story, which may use psychology as well as forensic science in order to determine the perpetrator?

That might explain the enduring popularity now, but I’m not sure that it adequately explains the popularity of those stories through all the years before DNA and CCTV. I think that people look for a hero that is always one step ahead (or two or three like Holmes!), and also who has a sense of justice. He should be something of a guardian angel, or a Court of Last Resort. However, I have seen a very disturbing pollution of Holmes in recent years, as many people add in various flaws in stories about him that were never in the original Canon – extreme drug addiction, sociopathic or murderous behaviours, attempts to put him on the Autism scale, or to make him manic-depressive, a total lack of social or grooming skills, a general inept disfunction, etc – in an attempt to have a broken Holmes with whom they can identify. Holmes doesn’t need to be broken. He is a hero. And we don’t need to drag him down to identify with him. In the original stories it’s Watson that we identify with – a brave, steadfast, and intelligent friend, doctor, husband, and former soldier –the everyman that shows us Holmes through his lens. That’s how I want to see Our Heroes, and not as something sad and struggling.

What about the role of sidekick in the Holmes and Thorndyke series? Watson versus Jervis. Who makes the better narrator, and who is the more appealing character, in your view?

No question, I choose Watson as the better narrator, because before Watson appeared, there had been nothing really like that, and all that follow are just imitators. There’s a reason why so many of the other narrators of The Great Detectives’ adventures – Dr. Parker, Captain Hastings, Archie Goodwin, Dr. Jervis – are referred to as their Watsons. Even Dupin’s unnamed friend and narrator, who came before Watson, pales when compared with Watson. There are quite a few who argue that The Canon is really Watson’s story, since we see it all from his perspective, and he’s such an interesting, brave, compassionate, and decent character. We need him to filter our view of Holmes. I don’t think anyone will ever argue that some of the Poirot stories are actually Hastings stories.

No question, I choose Watson as the better narrator, because before Watson appeared, there had been nothing really like that, and all that follow are just imitators. There’s a reason why so many of the other narrators of The Great Detectives’ adventures – Dr. Parker, Captain Hastings, Archie Goodwin, Dr. Jervis – are referred to as their Watsons. Even Dupin’s unnamed friend and narrator, who came before Watson, pales when compared with Watson. There are quite a few who argue that The Canon is really Watson’s story, since we see it all from his perspective, and he’s such an interesting, brave, compassionate, and decent character. We need him to filter our view of Holmes. I don’t think anyone will ever argue that some of the Poirot stories are actually Hastings stories.

And while Dr. Jervis is most often associated with Dr. Thorndyke, there are actually a number of other narrators of the various Thorndyke stories besides Jervis, including Doctors Berkely, Jardine, and Strangeways, lawyer Robert Anstey, and even Nathaniel Polton, Thorndyke’s crinkly-faced assistant. (Polton is something between Thorndyke’s Q and a forensic house elf). In many cases, Freeman seemed to need to use a different narrator because he’d already allowed Jervis to meet his wife in the very first book, and in order to have a romance bloom in subsequent tales, he needed new and unmarried narrators. (None of these other narrators can equal Watson either.)

If you were a TV producer making a series of Thorndyke episodes, closely based on the originals, who would you pick to play Thorndyke (and the other principal characters)?

That’s a tough question, because I don’t usually pay attention to actors. Instead, I’m interested in characters. I’ve never in my life watched a film because it had a certain actor in it. I either watch because it’s about a character that I care about, or because the story sounds interesting. In so many cases where a film has been made about one of my “book friends” (as my son called them when he was little), the actor simply isn’t right. He or she may get close, but it’s never completely true, for various reasons – physical variations, choices by the screenwriters/adapters to service their own swollen egos over the original material, etc.

Dr. Thorndyke was born in 1870, and his adventures span from when he’s in his late twenties to his sixties. However, when he’s about thirty is when he’s in his prime, so we’d need an actor of around that age. Often when an actor is cast as Holmes, he is far too old for the part. In every Canonical adventure but one, Holmes was under fifty, and for a good many of them he was in his thirties, with Watson only a couple of years older. The elderly versions of Holmes and Watson portrayed onscreen are often simply wrong.

Thorndyke is described as very handsome, and he’s usually in a good mood, smiling easily. He generally knows more about what’s going on than those around him, and the actor playing him needs to have a twinkle in his eye when watching others try and figure out the solution. John Neville played him in a rare 1970’s televised version of one of the stories, and he was somewhat close, but still not quite right. (There’s something about Neville, as seen in his portrayal of Holmes in A Study in Terror [1965] that’s a little to breathlessly enthusiastic.)

Jervis is about the same age as Thorndyke – they were friends in school. We don’t know a lot about him, except that he’s tall and apparently handsome too, although life had beaten him down a little bit before he began working with Thorndyke. Marchmont, a lawyer who appears frequently, is seemingly in his sixties, and Superintendent Miller is probably a few years older than Thorndyke. Polton is older – he seems old when we first meet him, and he stays that way – and is a small fellow with a crinkly-faced smile. Then there are the other doctors (and a lawyer) who sometimes narrate the Thorndyke adventures – Berkely, Jardine, Strangeways, and Anstey. They are all a bit younger than Thorndyke, and would need to be cast as well.

If he weren’t already in his sixties and retired, Daniel Day Lewis would make a good Thorndyke. (I’ve long made the case elsewhere that he should play Holmes in the World War I years. Just take a look at him in 2017’s The Phantom Thread to see how right he physically looks for the part.) However, after giving this way too much thought, I simply can’t pick anybody. I don’t know actors that well, until they get cast in something that I want to see, and then I judge whether they’re right or not.

Stephen Moffat, co-creator of the BBC SHERLOCK series says that other detectives have cases, Sherlock Holmes has adventures. Where does Thorndyke fit on that scale?

Thorndyke is much more on the “case” end of the spectrum. Those stories are generally very workmanlike, with Thorndyke gathering evidence that is in plain sight of the narrator and the reader, but refusing (with a smile) to interpret or explain it before he’s ready. Then he lays it out, often in a Coroner’s Court, and suddenly it’s very obvious. When something adventurous happens – such as Thorndyke being sent a poisoned cigar by a murderer, or being trapped in a locked secret chamber with a container of gaseous poison that might kill him at any minute, it’s much more of an unexpected treat, as one is conditioned to expect that he’s simply going to be steadily gathering evidence to build his case.

What augments the pleasure of reading these evidence-gathering stories is that in a number of these cases, we already know who committed the crime, and we’re simply seeing how Thorndyke builds his web, one strand at a time, undoing what the criminal thought was unsolvable. The author, R. Austin Freeman, invented the “Inverted Detective Story”, in which the reader sees the crime occur, and the real mystery is how will Thorndyke uncover the truth. This was later used by Columbo in that long-running television series.

Any thoughts on who will be the next “Marcum discovery”?

First up is finishing the re-issues of the Thorndyke books (along with the various ongoing Holmes projects that I write and edit). Later this year, three more volumes will arrive (to complement the first two volumes from late 2018, which consisted of the first half of the short stories and three novels.) The next set will be the rest of the short stories, and six more novels. Then, during 2020, I plan to release the final twelve Thorndyke novels in four more books, making it a nine-volume set of The Complete Dr. Thorndyke. That, along with all the Sherlock Holmes writing and editing on my plate, should keep me busy.

After that . . . I have an idea. I reissued all of the Martin Hewitt stories back in 2014, although some people didn’t like it, as I reworked them into early Holmes stories, set in Montague Street before Holmes moved to Baker Street. Then I spent much of 2018 to bring back all of the original Solar Pons stories. After that came Thorndyke, and now I’m thinking about doing the same for another detective who has faded from the limelight. However, he’s less like Sherlock Holmes and more like Ellery Queen, one of my other heroes – that may be a clue – and I don’t know what the reaction to that might be from Sherlockian publishers. Hewitt, Pons, and Thorndyke all have strong Holmesian connections, so that was an easier idea to sell. However, there’s plenty of time for that later. First I have to finish up Thorndyke – but what a great way to spend some of my time! I invite everyone to wander to his chambers at 5A King’s Bench Walk and get to know him!

Thanks very much for this opportunity!

Thank you for all these answers.

To find out more about David Marcum’s work on detective fiction, simply type his name into your local Amazon site.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Woman Who Fooled The World: Belle Gibson’s Cancer Con, and the Darkness at the Heart of the Wellness Industry by Beau Donelly

The Woman Who Fooled The World: Belle Gibson’s Cancer Con, and the Darkness at the Heart of the Wellness Industry by Beau Donelly

I’ve picked out ten stories, and the 96-page book will be on sale soon. I’ve produced it as the same pocket size (4″ x 6″ or 101mm x 152mm) as the

I’ve picked out ten stories, and the 96-page book will be on sale soon. I’ve produced it as the same pocket size (4″ x 6″ or 101mm x 152mm) as the

But David has many other strings to his bow, and one of them is an interest in

But David has many other strings to his bow, and one of them is an interest in  The short answer is Dr. John Thorndyke, although it pains me to pick him over my hero, Sherlock Holmes. Having grown up around detectives and policemen (see below), I know that their disdainful attitude toward private detectives and amateurs that is portrayed in books and film is accurate. The police have a procedure that must be followed in order to document everything to make a court case that can’t be picked apart. The chain of evidence is sacred – or supposed to be that way. Also, there’s a feeling that if someone could really do the job, they’d be on the official force. Private detectives are usually a joke at best to the police in the real world.

The short answer is Dr. John Thorndyke, although it pains me to pick him over my hero, Sherlock Holmes. Having grown up around detectives and policemen (see below), I know that their disdainful attitude toward private detectives and amateurs that is portrayed in books and film is accurate. The police have a procedure that must be followed in order to document everything to make a court case that can’t be picked apart. The chain of evidence is sacred – or supposed to be that way. Also, there’s a feeling that if someone could really do the job, they’d be on the official force. Private detectives are usually a joke at best to the police in the real world. My dad had several notable cases over his career, and one was written up in a “True Crime” type magazine, but one big career accomplishment was that he was the first to use Dr. William Bass, the world-famous forensic anthropologist, as a consultant related to dead bodies, back when Dr. Bass was simply a college professor. When he retired, my dad received a commendation from the state for his entire career, including having that idea to involve Dr. Bass in a case. This involvement led to more work of the same type with other agents, and eventually Dr. Bass became so intrigued that he created “The Body Farm”, a world-famous site where decomposition of human remains can be studied under all types of conditions. It’s located about fifteen miles from where I live.

My dad had several notable cases over his career, and one was written up in a “True Crime” type magazine, but one big career accomplishment was that he was the first to use Dr. William Bass, the world-famous forensic anthropologist, as a consultant related to dead bodies, back when Dr. Bass was simply a college professor. When he retired, my dad received a commendation from the state for his entire career, including having that idea to involve Dr. Bass in a case. This involvement led to more work of the same type with other agents, and eventually Dr. Bass became so intrigued that he created “The Body Farm”, a world-famous site where decomposition of human remains can be studied under all types of conditions. It’s located about fifteen miles from where I live. No question, I choose Watson as the better narrator, because before Watson appeared, there had been nothing really like that, and all that follow are just imitators. There’s a reason why so many of the other narrators of The Great Detectives’ adventures – Dr. Parker, Captain Hastings, Archie Goodwin, Dr. Jervis – are referred to as their Watsons. Even Dupin’s unnamed friend and narrator, who came before Watson, pales when compared with Watson. There are quite a few who argue that The Canon is really Watson’s story, since we see it all from his perspective, and he’s such an interesting, brave, compassionate, and decent character. We need him to filter our view of Holmes. I don’t think anyone will ever argue that some of the Poirot stories are actually Hastings stories.

No question, I choose Watson as the better narrator, because before Watson appeared, there had been nothing really like that, and all that follow are just imitators. There’s a reason why so many of the other narrators of The Great Detectives’ adventures – Dr. Parker, Captain Hastings, Archie Goodwin, Dr. Jervis – are referred to as their Watsons. Even Dupin’s unnamed friend and narrator, who came before Watson, pales when compared with Watson. There are quite a few who argue that The Canon is really Watson’s story, since we see it all from his perspective, and he’s such an interesting, brave, compassionate, and decent character. We need him to filter our view of Holmes. I don’t think anyone will ever argue that some of the Poirot stories are actually Hastings stories.

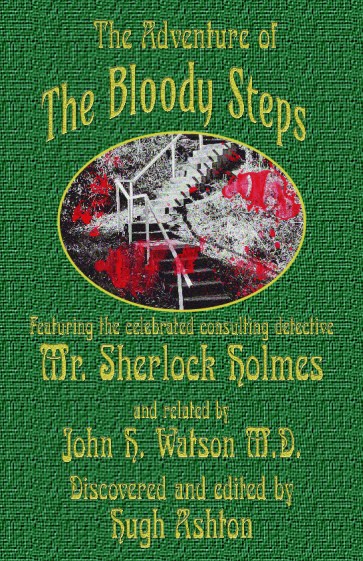

On June 17, 1839, the body of Christina Collins, who had been raped and murdered by the crew of the canal barge on which she was travelling from Liverpool, was carried up “The Bloody Steps” in Rugeley, Staffordshire.

On June 17, 1839, the body of Christina Collins, who had been raped and murdered by the crew of the canal barge on which she was travelling from Liverpool, was carried up “The Bloody Steps” in Rugeley, Staffordshire. Today, June 17, 2019, being 180 years after the discovery of Collins’ body, the story of Sherlock Holmes’ Rugeley investigations is officially published and available for sale. The story has been edited by Hugh Ashton, widely regarded as one of the most accomplished narrators of the exploits of the celebrated sleuth.

Today, June 17, 2019, being 180 years after the discovery of Collins’ body, the story of Sherlock Holmes’ Rugeley investigations is officially published and available for sale. The story has been edited by Hugh Ashton, widely regarded as one of the most accomplished narrators of the exploits of the celebrated sleuth.